Rendering untrusted HTML email, safely

One of the earliest core features we built in Close was our email sync feature, which allows Close to automatically pull in email communication between your sales team and your sales contacts and display them for your team to see. We present a unified timeline of all communication (emails, calls, SMS, etc.) with a sales lead in one place for your team.

This feature required that we build a way to display email in our web app – safely, without security concerns that typically come with naively rendering untrusted HTML (Stored XSS Attacks).

We launched our ability to display synced HTML email in 2014, however the technical side of it is still very relevant and (I think) interesting since our approach is not one that I've seen widely used.

In the end, we found a way to, exclusively on the client-side (in web browsers), render untrusted HTML email safely inside our single-page application (written originally with Backbone.js, now mostly React). Here we'll discuss a few approaches we had to consider and how we solved this problem.

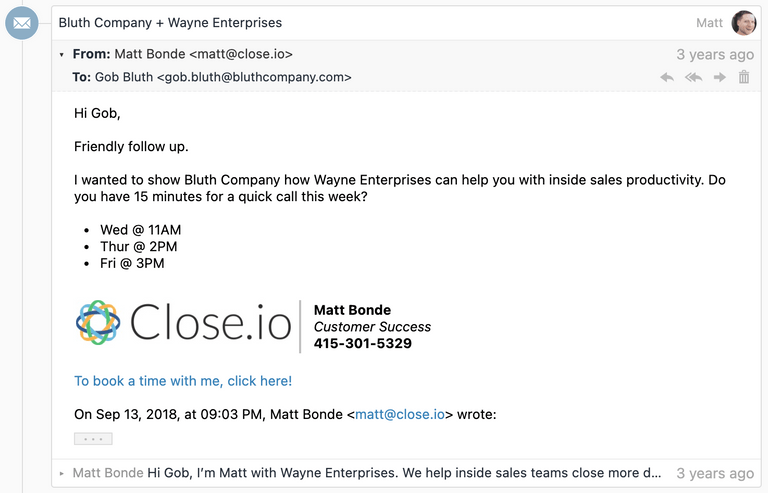

For example, we can display an IMAP-synced email thread like this:

HTML vs Plaintext?

While many emails do come with a plaintext variant, we had to immediately dismiss the idea of only displaying plaintext email, as convenient as that would have been from a security perspective. Many emails don't have a reasonable plaintext alternative, and users simply expect to be able to view HTML formatted email as they were designed.

Some emails only have a plaintext variant. In those cases we can render the

plaintext content pretty simply in our web app: effectively just convert new

lines into <br> tags and convert URLs into links.

But most of the interesting engineering/security concerns are around rendering untrusted HTML content (in this case, email content) safely, which is where the remainder of this blog post will focus.

Main goals and concerns

Our main goals were the following:

- Display HTML email, not just plaintext

- Display "full" HTML email. We care about much more than just a few simple tags

like

<b>and<i>, but rather want to support displaying sophisticated email styles (including customstyletags) that you often see in well-designed HTML email newsletters, calendar invitations, etc. - We want to render emails within our web application, without any conflicts of our CSS leaking in or the email CSS leaking out.

- In addition to CSS styles, we also want to display images, expect links to work, etc.

- Most important: Do not let any JavaScript run. Otherwise we run the risk of an attacker taking over our user's Close account by stealing cookies, or a number of other Very Bad™️ things.

Finding a solution…

Saying No to HTML Sanitization

While there may be some rock-solid libraries out there that can take untrusted HTML content and make it completely safe for rendering in HTML, there were a lot of potential downsides to this idea.

First off, in 2014, we didn't immediately trust any of them. HTML sanitization libraries often rely on parsing HTML with regex, which is a notoriously bad idea. We absolutely didn't want to be trying to maintain a library like this ourselves, or have to worry about some unhandled edge case that could lead to a major security vulnerability.

Additionally, unlike other use cases (e.g. rendering a blog comment which may contain just some basic markup for bolding text), we felt like we needed to render complex (heavily styled) HTML emails properly, just like you'd see in Gmail or other modern email clients, so we couldn't default to a tiny whitelist of tags or supported attributes.

Finally, HTML sanitization on its own wouldn't be enough, because we want to render the email within an existing web app, and we don't want its styles affecting the styles of the rest of the web app. There's a well-known solution to this – iframes – that we could have used to help here.

Once we explored iframes, however, we realized they could do everything we needed already on their own…

What can iframes do for us?

Most web developers know that an <iframe> can render a web page in a fairly

isolated fashion. Certainly they can solve the issue of our web app styles

incorrectly affecting an email's styles (or vice versa).

But we still have that pesky issue of JavaScript.

Uncommon but helpful iframe attributes

There are a number of lesser known iframe attributes that can be very helpful. Let's take a look at a few.

srcdoc

Most commonly iframes point to a src webpage URL – either on the same origin

or different origin. But since Close is a Single Page Application and our

frontend would already be fetching data about the email from our

REST API (and could include the email body

itself), we discovered that this attribute allowed us to inject HTML content

into an iframe (with all the typical iframe benefits) without needing that

content to be served by a separate page.

So rather than having to do something like:

<iframe src="/email/body/?email_id=EMAIL_ID_HERE">

... which would have required us to setup an additional endpoint, we could simply display the HTML we already had:

<iframe srcdoc="UNTRUSTED_HTML_HERE">

Neither approach is particularly more or less secure than the other. Both make

you still think about "what about script execution" and consider the "same

origin" vs. "different origin" options (e.g. we might have needed a separate

domain and then have to pass some kind of token for authentication). We chose

srcdoc because it worked and was easiest for our setup.

For the value that we inject into the srcdoc, we actually wrap the HTML email

in a little HTML, with two main goals:

- Give email bodies some sane default styles, and make them fit into the look-and-feel of our web app by default.

- Put

target="_blank"on all links by default (via a<base>tag), since we never want a user clicking an email link to load a new webpage in the iframe, and this is also a convenient way for us to apply this behavior to all links without having to traverse the email's HTML. - Apply a

Content-Security-Policy<meta>tag instructing the iframe document to avoid executing any JavaScript whatsoever. (If we used a hosted page withsrcinstead ofsrcdoc, this would be done with an HTTP Header instead).

<html>

<head>

<meta http-equiv="Content-Security-Policy" content="script-src 'none'" />

<base target="_blank" />

<style>

body {

margin: 0;

font:

13px -apple-system,

system-ui,

'Segoe UI',

Roboto,

Oxygen-Sans,

Ubuntu,

Cantarell,

'Helvetica Neue',

sans-serif,

'Apple Color Emoji',

'Segoe UI Emoji',

'Segoe UI Symbol',

sans-serif;

overflow-y: hidden;

}

html:not(.x),

body:not(.x) {

height: auto !important;

}

p:first-child {

margin-top: 0;

}

p:last-child {

margin-bottom: 0;

}

a[href] {

color: #3781b8;

text-decoration: none;

}

a[href]:hover {

text-decoration: underline;

}

blockquote[type='cite'] {

margin: 0 0 0 0.8ex;

border-left: 1px #ccc solid;

padding-left: 1ex;

}

img {

max-width: 100%;

}

ul,

ol {

padding: 0;

margin: 0 0 10px 25px;

}

ul {

list-style-type: disc;

}

</style>

</head>

<body>

${bodyHtml}

</body>

</html>sandbox

This attribute is the heart of our security model. By adding this attribute, it

adds a whole bunch of restrictions to the iframe document, including preventing

any JavaScript from running! Learn more about what's blocked

here

and here.

The sandbox attribute allows you to opt back in specific behaviors that are

blocked by default. We only allow:

allow-popups– We addtarget="_blank"to all of them.allow-popups-to-escape-sandbox- So that external webpages opened via a link actually function properly.allow-same-origin– We need this for our web app to detect the height of iframe's content. This would be dangerous (and defeat the purpose ofsandbox) if we also allowed scripts to run by also includingallow-scripts, however it's harmless on its own.

csp

We add a Content Security Policy to the iframe with a value of

script-src 'none' as an additional mechanism to avoid any JavaScript from

running in the iframe. This is mostly duplicative with sandbox but provides an

extra layer of protection in

browsers that support

it.

As you can see, we have some overlap in coverage here (e.g. 3 separate features to avoid JavaScript running). We have learned of particular browser bugs where there were temporary limitations in any one of these indvidiual approaches. A reminder that security in layers is often best.

Bringing it together...

<iframe

srcdoc="{{UNTRUSTED_HTML_HERE}}"

sandbox="allow-popups allow-popups-to-escape-sandbox allow-same-origin"

csp="script-src 'none'"

/>Handling unsupported browsers

As soon as we made the decision to rely on <iframe sandbox> as our primary

safety mechanism, we also had to consider users with browsers who didn't have

this safety mechanism, so that we didn't put their accounts at risk. Feature

detection to the rescue:

// Don't show HTML at all if they are using a browser that doesn't support <iframe sandbox>

// since our security model relies on it to prevent XSS.

// (And the basic functionality relies on <iframe srcdoc>)

const iframe = document.createElement('iframe');

const isHtmlEmailSupported = 'sandbox' in iframe && 'srcdoc' in iframe;Based on this, we can make sure we only display the plaintext email variant (if one exists) or else render a message like "Your browser does not support displaying email content."

Known limitations

One can envision additional enhancements where we would want to parse and modify the email HTML before rendering it. One example would be if we wanted to try to rewrite and proxy all image URLs (similar to Gmail) to protect our users' privacy.

Similarly, we do have a problem where browsers will show a Mixed Content warning

(since our site is https://) after you display an email that includes an

<img> with an http:// src. Those warnings are still fairly unobtrusive,

however, but ultimately we should proxy them to be served over https.

So while we may one day layer in additional HTML parsing measures (either

client-side or server-side), and could decide to switch from an

<iframe srcdoc> to <iframe src>, the other security features mentioned here

would still likely play an important part of safely rendering HTML email.

Lots of other details to get right

There were a lot of other details to get right. Each of them could deserve their own blog post, but here is a summary:

- We have to convert "inline" images (images that are embedded within the email itself, not referencing an external URL) to be displayable by the web browser.

- We have to deal with understanding quoting parts. We wrote quotequail for this. (Mailgun later open sourced a similar library called talon). You can see in the screenshot at the top of this post a little "..." button where the quoted part of the email is collapsed by default, but expandable.

- We want to avoid the "extra scrollbar" issue you typically experience with iframes, so we carefully (this is surprisingly tricky) detect the height of the iframe email contents and then set the iframe to that height, giving it a seamless look on the page.

- We need to consider how composing email works too. We needed a WYSIWYG editor for HTML Email that also prevents any XSS. We currently use Froala Editor for this, after having tested many editors for security.

Thoughts?

Can you find any flaws in our email rendering security model? Our product and approach has been audited by third party security firms, however we always appreciate any reports of security vulnerabilities at security@close.com.

Feel free to hit me up at @philfreo with any comments or questions!

– Phil Freo