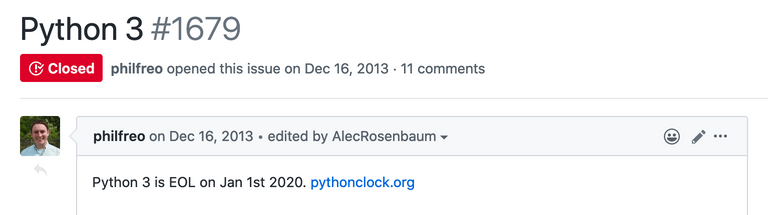

Python 3

First some context — our largest repo is on the order of hundreds of thousands of lines of code, written over the course of the last decade. Not a huge codebase, but also not small. Our Python 3 issue has been open since Dec 2013, and we finally closed it in April 2020. In all fairness, we only prioritized this project starting in mid-2019. This post is a deep dive into what we think our most interesting issue was, plus a few things that surprised us.

MongoDB.

We use MongoDB to store a lot of our data. It was hip in 2013, and still

houses terabytes of our customers’ data.

Mongoengine (a MongoDB ORM) is

even maintained by one of us! What started

with a flaky test during our Python 3 upgrade turned into a deep dive into how

Python dictionaries intersect with mongoengine, pymongo, and bson.

But first, some background on Python dictionaries

In 2011, a CVE was published

that showed you could DDoS by strategically picking dictionary keys for poor

performance. As a result, Python added PYTHONHASHSEED, which can be set to

"salt" hash keys with random values. See the

official 3.5 docs

for details.

In Python 2.7, PYTHONHASHSEED defaults to 0 (disabled) but can be set to

random to make key order inconsistent between executions. By default,

dictionary key order is random and consistent:

$ python2 -c "print(dict([(i,idx) for idx, i in enumerate('abcdef')]))"

{'a': 0, 'c': 2, 'b': 1, 'e': 4, 'd': 3, 'f': 5}

$ python2 -c "print(dict([(i,idx) for idx, i in enumerate('abcdef')]))"

{'a': 0, 'c': 2, 'b': 1, 'e': 4, 'd': 3, 'f': 5}

$ python2 -c "print(dict([(i,idx) for idx, i in enumerate('abcdef')]))"

{'a': 0, 'c': 2, 'b': 1, 'e': 4, 'd': 3, 'f': 5}In Python 3.5, PYTHONHASHSEED defaults to random but can be set to 0

(disabled) to make key order consistent between executions. By default,

dictionary key order is random and intentionally inconsistent:

$ python3 --version

Python 3.5.2

$ python3 -c "print(dict([(i,idx) for idx, i in enumerate('abcdef')]))"

{'d': 3, 'a': 0, 'f': 5, 'e': 4, 'b': 1, 'c': 2}

$ python3 -c "print(dict([(i,idx) for idx, i in enumerate('abcdef')]))"

{'a': 0, 'd': 3, 'c': 2, 'f': 5, 'b': 1, 'e': 4}

$ python3 -c "print(dict([(i,idx) for idx, i in enumerate('abcdef')]))"

{'a': 0, 'b': 1, 'f': 5, 'e': 4, 'c': 2, 'd': 3}Note that disabling PYTHONHASHSEED in Python 2.7 and Python 3.5 yields

different key orders:

$ PYTHONHASHSEED=0 python2 -c "print(dict([(i,idx) for idx, i in enumerate('abcdef')]))"

{'a': 0, 'c': 2, 'b': 1, 'e': 4, 'd': 3, 'f': 5}

$ PYTHONHASHSEED=0 python3 -c "print(dict([(i,idx) for idx, i in enumerate('abcdef')]))"

{'b': 1, 'c': 2, 'e': 4, 'a': 0, 'f': 5, 'd': 3}

$ python3 --version

Python 3.5.2Even when PYTHONHASHSEED=0 in Python 3.5, the key order isn't consistent if

you insert items in different orders:

$ python2 --version

Python 2.7.12

$ PYTHONHASHSEED=0 python2 -c "print(dict([(i,idx) for idx, i in enumerate('abcdef')]))"

{'a': 0, 'c': 2, 'b': 1, 'e': 4, 'd': 3, 'f': 5}

$ PYTHONHASHSEED=0 python2 -c "print(dict([(i,idx) for idx, i in enumerate('fedcba')]))"

{'a': 5, 'c': 3, 'b': 4, 'e': 1, 'd': 2, 'f': 0}

$ python3 --version

Python 3.5.2

$ PYTHONHASHSEED=0 python3 -c "print(dict([(i,idx) for idx, i in enumerate('abcdef')]))"

{'b': 1, 'c': 2, 'e': 4, 'a': 0, 'f': 5, 'd': 3}

$ PYTHONHASHSEED=0 python3 -c "print(dict([(i,idx) for idx, i in enumerate('abcdef')]))"

{'b': 1, 'c': 2, 'e': 4, 'a': 0, 'f': 5, 'd': 3}

$ PYTHONHASHSEED=0 python3 -c "print(dict([(i,idx) for idx, i in enumerate('fedcba')]))"

{'c': 3, 'b': 4, 'a': 5, 'f': 0, 'e': 1, 'd': 2}Starting in Python 3.6, dictionaries are insertion-ordered (due to changes in the underlying implementation):

$ python3 --version

Python 3.6.9

$ python3 -c "print(dict([(i,idx) for idx, i in enumerate('abcdef')]))"

{'a': 0, 'b': 1, 'c': 2, 'd': 3, 'e': 4, 'f': 5}Note that this became part of the official spec in Python 3.7.

You mentioned a flaky test earlier?

Yeah, we’re getting to that. But first, let’s answer this question: why does Python dictionary ordering impact MongoDB at all? Because in MongoDB, objects are ordered. So :

{'a': 'a', 'b': 'b'} != {'b': 'b', 'a': 'a'}Ok… and? Yodawg because in MongoDB, you put documents inside your documents, i.e.

{'_id': 'obj_xxx', 'example': {'a': 'a', 'b': 'b'}}I’m still not getting why this is relevant. Because sometimes we directly or indirectly query by those documents inside those other documents. For example, the following query is valid:

MyDoc.objects.filter(example={'a': 'a', 'b': 'b'})Direct filtering on documents like that above example probably isn't very

common, but some fields internally use objects/dictionaries to represent,

persist, and query for their state. For example:

mongoengine.fields.GenericReferenceField.

GenericReferenceField references a specific id, collection, and _cls.

That way, we can automatically de-serialize any DBRef(collection, id) into its

corresponding mongoengine document. When serializing in to_mongo we need to

store a few different values, so we use an object:

{

_cls: 'SomeClass',

_id: 'someclass_xxxx'

generic_reference: {_cls: 'MyClass', _ref: DBRef('collection', 'someid_xxx')},

}In our Python-land, you filter on generic_reference just by passing in some

object, so for the object above a query might look like:

my_obj = MyDocument.objects.get(pk='someid_xxx')

ref = OtherDocument.objects.filter(generic_reference=my_obj)This ends up going down through mongoengine, calling to_mongo on the

GenericReferenceField and down into pymongo code. Since

GenericReferenceField returns a dictionary, we have a few problems:

- Different versions of Python will produce different key orders (which according to MongoDB isn’t the same value)

- Python 3.5's dictionary ordering intentionally isn't consistent within itself

- Even if dictionary ordering is consistent, any changes made going forward are going to need to match the (consistent but random) dictionary ordering behavior of Python 2.7

If this isn’t solved correctly, there could be a few different classes of issues:

- Queries that operate on documents with nested objects will (literally) randomly work or not work

- If we insert documents with nested objects that don't match the ordering of

previously inserted nested objects, we end up with major data consistency

issues

- If this happens, it can only be fixed with a data migration

- Until a data migration is run, queries will randomly work or not work even after reverting changes

So this brings us back to our failing test

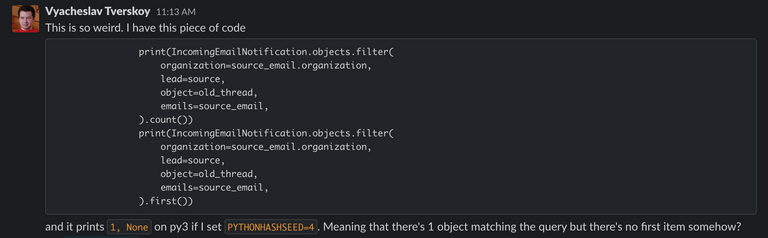

We thought we were relatively ready to move forward with our upgrade to Python 3.5. Our dependencies had all been upgraded and most of the surface level issues (re: 2000 failing unit tests) had been ironed out. We added a step in our continuous integration to run tests on Python 3.5 as well as Python 2 for all builds going forward. Then CI started failing intermittently, but only a small group of tests and only on Python 3. Weird. At first it was ignored, thought to just be intermittent failures related to networking, remote docker, etc. One of our engineers started digging deeper though:

That’s where the rabbit hole started, bringing us all the way down to where we

bottomed out before. The object field was a GenericReferenceField and

.first() emitted a different MongoDB query from .count(). Half the time our

underlying {_cls: 'MyDoc', _ref: DBRef('OtherDoc', id_xxxx'} object had its

keys in a different order from when it was inserted, because copying

dictionaries changes the key order in Python 3.5. Setting PYTHONHASHSEED

forced the hash randomization seed, which made the issue reproducible locally.

How did we fix it?

Well, fields that return objects don't always have to be dictionaries. In

MongoDB, dictionary order matters because it uses a binary representation called

BSON. When comparisons are done server-side, it just compares the binary

directly and doesn't actually parse it. Unfortunately, keys aren't sorted when

going between dictionaries and BSON. But, we can directly work with BSON

objects in Python that have the same type of ordering behavior. Generally

speaking, it seems that these objects are interchangeable when working within

mongoengine/pymongo code.

In more recent versions of mongoengine than what we were using, the to_mongo

code that returned a dictionary instead returned a

SON

object

(with guaranteed key ordering).

id_ = id_field.to_mongo(id_)

collection = document._get_collection_name()

ref = DBRef(collection, id_)

return SON((("_cls", document._class_name), ("_ref", ref)))Our options were:

- Convert the closeio

mongoenginefork to useSONeverywhere in place of dictionaries (matching 2.7 ordering), then go to Python 3.5. - Set

PYTHONHASHSEED=0when upgrading to Python 3.5.- Tests will pass and will be consistent going forward, but will not be backwards compatible.

- Requires a migration where data is pulled out then stuck back in for each field where this matters.

- Go to Python 3.6 where keys are ordered, changing the order of dictionaries

where needed to match 2.7 ordering.

- Spoiler, this is the option we picked.

Note that dictionaries are copied all over the place within mongoengine and

pymongo (each .filter call on a QuerySet clones it). Going to Python 3.5

retains some risk that at some point SON will be converted into a dictionary

during a copy operation and lose ordering. Or even that the ordering will by

chance be correct but at a deeper layer the keys are renamed from their alias to

the MongoDB-specific value (or are otherwise restructured). It's also possible

that there will be some other case where the dictionary can’t be exchanged for a

SON object. In those cases, using an OrderedDict will likely not help

because of all the cloning going on under the hood.

We chose to go to Python 3.6, subclassing our field to return SON with

ordering matching what was generated by Python 2.7. We also audited our

codebase, looking for anywhere else that might have a similar issue. So far, it

seems that our fixes worked (knock on wood). We really lucked out here in that

3.5 exposed this issue before it hit production. Our unit tests did not test

generating and consuming data on different Python versions, so if we had decided

to go directly to 3.6 this likely would have caused data consistency issues

requiring much more effort to backfill/fix.

Some other fun Python 2/3 footguns

Hashing

crc32 hashing changed between Python 2 and Python 3, but only sometimes.

$ python3 -c "import zlib; print(zlib.crc32(b'example1'))"

3808595449

$ python2 -c "import zlib; print(zlib.crc32(b'example1'))"

-486371847

$ python2 -c "import zlib; print(zlib.crc32(b'example'))"

1861000095

$ python3 -c "import zlib; print(zlib.crc32(b'example'))"

1861000095Note that this is documented:

Changed in version 3.0: Always returns an unsigned value. To generate the same numeric value across all Python versions and platforms, use

crc32(data) & 0xffffffff.

None < 0

wat

$ python2 -c "print(None < 0)"

True

$ python3 -c "print(None < 0)"

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<string>", line 1, in <module>

TypeError: '<' not supported between instances of 'NoneType' and 'int'Unicode

Yeah, I know this is the big one but it’s still tricky. We do a lot of email

parsing, which gave us lots of edge cases going back and forth between bytes

and unicode, with lots of email-client-generated bad data in a variety of

languages.

$ python2 -c "print(str(b'example'))"

example

$ python3 -c "print(str(b'example'))"

b'example'

$ python2 -c "print(u'example'.decode())"

example

$ python3 -c "print(u'example'.decode())"

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<string>", line 1, in <module>

AttributeError: 'str' object has no attribute 'decode'

$ python2 -c "print(u'∑xåmple…'.encode())"

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<string>", line 1, in <module>

UnicodeEncodeError: 'ascii' codec can't encode characters in position 0-2: ordinal not in range(128)

$ python3 -c "print(u'∑xåmple…'.encode())"

b'\xe2\x88\x91x\xc3\xa5mple\xe2\x80\xa6'

$ python2 -c "print(repr(b'\xb0\xf8\xb0\xed\xb9\xae'.decode('utf8', errors='ignore')))"

u'\ude6e'

$ python3 -c "print(repr(b'\xb0\xf8\xb0\xed\xb9\xae'.decode('utf8', errors='ignore')))"

''For more on the last example, see the last paragraph on surrogate characters here.

Properties

Documented, but still weird:

$ python2 -c "

class C:

@property

def someattr(self): raise RuntimeError('This should be AttributeError')

print(hasattr(C(), 'someattr'))

"

False

$ python3 -c "

class C:

@property

def someattr(self): raise RuntimeError('This should be AttributeError')

print(hasattr(C(), 'someattr'))

"

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<string>", line 6, in <module>

File "<string>", line 4, in someattr

RuntimeError: This should be AttributeErrorPython 2 catches all exceptions and returns False, whereas Python 3 only

catches AttributeError's.

Further reading here.

Timezones

It turns out that Python 3 changed some assumptions about timezones. Now the system locale’s timezone will impact naive datetime timezone conversions:

$ python2 -c "import datetime; import pytz

print(datetime.datetime(2020, 1, 1).astimezone(pytz.UTC))

"

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<string>", line 2, in <module>

ValueError: astimezone() cannot be applied to a naive datetime

$ python3 -c "import datetime; import pytz

print(datetime.datetime(2020, 1, 1).astimezone(pytz.UTC))

"

2020-01-01 05:00:00+00:00More details here.

python-future

Don’t be fooled into thinking

python-future will address all of your

edge cases. It’s a godsend of an OSS project that handles a huge portion of the

boilerplate changes, but there’s only so much you can do with an automated tool

operating on a dynamic language.

Forks

It’s easy to fork a repo to make just that one simple fix you’ll eventually push back upstream. It’s hard to undo dozens of these forks when you need to upgrade back to upstream 3 years later.

Dependencies and PyPi Tags

A very significant portion of the time spent on this project was auditing dependencies, removing or upgrading where possible, and carefully keeping track of the latest version each dependency tests against. In our experience, PyPi tags generally had little bearings as to whether projects actually tested against their tagged versions.

If a project like this is in your future, don’t underestimate the time sink of this step.

Closing thoughts

We’re very happy to finally have our core services running Python 3, and are

still cleaning up all the artifacts of our upgrade. f-strings, native type

checking syntax, and long term support are all major wins!

Hit me up at alec.rosenbaum@close.com with any questions or comments :)