Introducing MongoMallard: A fast ORM based on MongoEngine

Introducing MongoMallard: A fast ORM based on MongoEngine

Here is how we minimized the response time of our application by rewriting parts of MongoEngine, the MongoDB ORM we were using. Since the new ORM is not fully backwards-compatible with MongoEngine, we are calling it MongoMallard. You can fork it here:

https://github.com/closeio/mongomallard

This post explains how we identified that MongoEngine was slowing down our application significantly and shows some technical details on the implementation of MongoMallard.

Identifying the issue

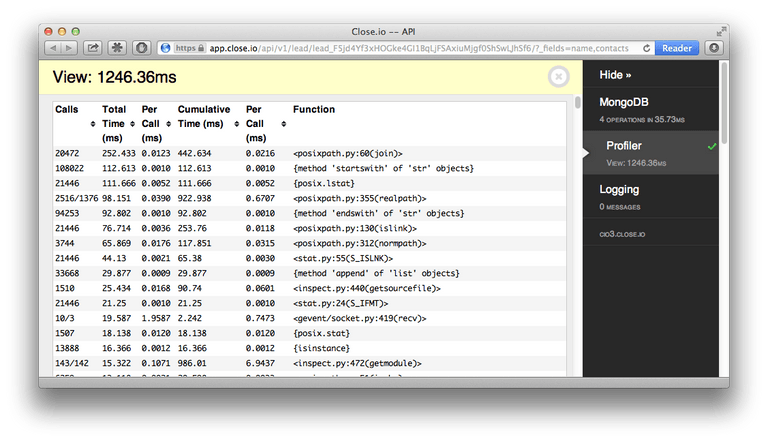

We started by profiling our API requests to see where slowdowns occured. A helpful tool was the flask-debugtoolbar which gives you a toolbar similar to the Django debug toolbar showing you profiling information and logging information. We extended the debug toolbar in our fork to allow for more customizations. Combined with flask-mongoengine we also got query profiling for MongoDB. The toolbar was set up so that only admins could see it.

When looking at the profiling view, we noticed many calls to the file system which were slow. However, nowhere in our code did we perform heavy file system operations. It turned out that a lot of time was spent preparing the toolbar itself, specifically generating tracebacks for the MongoDB panel.

We noticed that this also affected regular requests from non-admins where the toolbar wasn't shown. We fixed this problem by patching flask-mongoengine's operations tracker and by also making sure we uninstalled the tracker when it wasn't needed.

Below you can see the full toolbar subclass which also checks for admin permissions:

class ProtectedDebugToolbarExtension(DebugToolbarExtension):

debug_toolbar_class = CustomDebugToolbar

def __init__(self, app):

super(ProtectedDebugToolbarExtension, self).__init__(app)

self._needs_uninstall_tracker = MongoDebugPanel in DebugToolbar.panel_classes

def teardown_request(self, exc):

if self._needs_uninstall_tracker and request._get_current_object() in self.debug_toolbars:

from flask_mongoengine.operation_tracker import uninstall_tracker

uninstall_tracker()

super(ProtectedDebugToolbarExtension, self).teardown_request(exc)

def _show_toolbar(self):

from flask.ext.login import current_user

if self.app.debug or 'admin' in getattr(current_user, 'roles', []):

# check mimetype so we don't waste resources on non-html requests

if super(ProtectedDebugToolbarExtension, self)._show_toolbar() and \

request.accept_mimetypes.best_match(['text/html', 'application/json']) == 'text/html':

return True

elif '_debug' in request.args:

return True

return FalseIf you want to use the toolbar, you can simply install it with the following

line, where app is the Flask application object:

ProtectedDebugToolbarExtension(app)Here is our debug toolbar configuration:

DEBUG_TB_PANELS = [

'flask.ext.mongoengine.panels.MongoDebugPanel',

'flask_debugtoolbar.panels.profiler.ProfilerDebugPanel',

]

DEBUG_TB_INTERCEPT_REDIRECTS = False

DEBUG_TB_EXCLUDE_PATH_PATTERN = '^((?!\/api\/).)*$'

DEBUG_TB_ENABLED = True

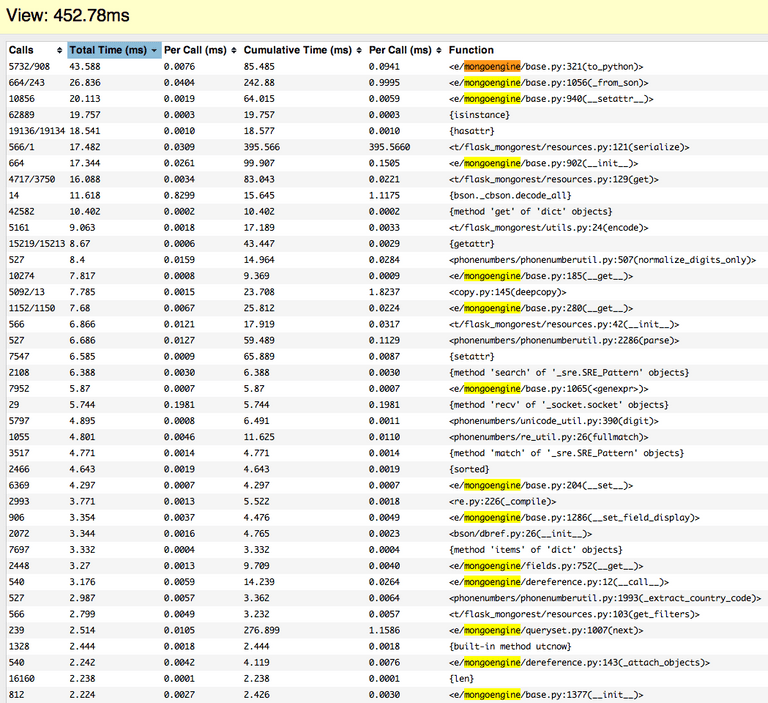

DEBUG_TB_PROFILER_ENABLED = TrueAfter making sure all MongoDB queries were optimized (by adding indexes or combining multiple queries on the same collection into one query), we discovered that a lot of time was spent in MongoEngine. Why?

How objects are loaded in MongoEngine

To understand why a lot of time was spent in MongoEngine, we investigated how objects from the database are loaded in MongoEngine. Let's say we load one of these big sales leads in our application. This is how you do it in MongoEngine:

lead = Lead.objects.get(pk='lead_F5jd4Yf3xHOGke4GI1BqLjFSAxiuMjgf0ShSwLJhSf6')Behind the scenes, MongoEngine invokes pymongo which is the lower-level Python

library that actually fetches the data from MongoDB. Since MongoDB documents are

encoded as BSON, pymongo parses the BSON and returns the data back as a Python

SON object. This is

done using a C implementation of BSON (which shows up as

bson._cbson.decode_all in the profiler) and is therefore very fast.

Afterwards, MongoEngine creates an object from the SON by passing it into its

_from_son function as follows:

lead = Lead._from_son(son)After timing this function we noticed that a lot of time was spent creating the document object from SON. The problem was that all fields were being evaluated, validated and converted into the appropriate Python objects. Most of the time we time we didn't access all properties of every object so evaluating all the fields was unnecessary (and limiting the fields we fetch from the database every time would involve a lot of work), and we could also assume that data in the database was already validated.

Hacking MongoEngine

We decided to rewrite the document class of MongoEngine to be much faster,

specifically when initializing objects. The idea was to not traverse the SON

object at all when initializing an object from the database. Instead, we would

lazily evaluate the fields when needed. The new _from_son method simply passes

the SON to the class constructor after determining the correct class (in case of

inheritance):

class BaseDocument(object):

# ...

@classmethod

def _from_son(cls, son):

# get the class name from the document, falling back to the given

# class if unavailable

class_name = son.get('_cls', cls._class_name)

# Return correct subclass for document type

if class_name != cls._class_name:

cls = get_document(class_name)

return cls(_son=son)The __init__ method assigns the SON to _db_data without doing any other

processing (values is empty if we initialize from the database):

def __init__(self, _son=None, **values):

"""

Initialise a document or embedded document

:param values: A dictionary of values for the document

"""

_set(self, '_db_data', _son)

_set(self, '_lazy', False)

_set(self, '_internal_data', {})

_set(self, '_changed_fields', set())

if values:

# ...We have a dictionary called _internal_data which stores the already evaluated

fields. Every line in the __init__ method was benchmarked to ensure fast

object initialization since this constructor may be called thousands of times

when fetching big objects.

The __get__ method of our field base class transforms the SON value into a

friendly Python type and assigns it to the _internal_data array before

returning. It is only called when we actually access a specific field.

class BaseField(object):

# ...

def __get__(self, instance, owner):

# ...

if not name in data:

# ...

try:

db_value = instance._db_data[db_field]

except (TypeError, KeyError):

value = self.default() if callable(self.default) else self.default

else:

value = self.to_python(db_value)

# ...

data[name] = value

return data[name]We've also gone through all the field classes and rewrote big parts of them, removing any code that might negatively affect performance.

Changing the way ReferenceField works

Let's say you are using the ReferenceField, which is stored as a reference to

another object (which may be in a different collection) in MongoDB:

class Lead(Document):

name = StringField()

class Contact(Document):

name = StringField()

lead = ReferenceField(Lead)If you fetched a Contact and tried to access the lead field, the following

would happen:

- MongoEngine would try to fetch the lead from the database

- If the lead existed, it would be returned

- If the lead didn't exist, a DBRef object with the non-existent lead ID would be returned.

This behavior had multiple disadvantages:

- If we just wanted to get the ID of the lead and not fetch the lead, we needed

to do

contact._data['lead'].id. - If we actually wanted to check if the lead existed and reference any fields,

the code would look like this:

if contact.lead and not isinstance(contact.lead, DBRef): # ...

That's why we changed the behavior. MongoMallard comes with two different reference fields:

ReferenceFieldwill return a lazy document. Lazy documents are fetched from the database only if a non-ID field is requested. Otherwise, an exception is raised. This has the advantage that we can docontact.lead.idwithout a database request.SafeReferenceFieldwill return a valid document orNone. It will never return an invalid reference. With aSafeReferenceFieldwe can simply doif contact.lead: # ...and don't have to worry about broken references.

Which one of the reference fields is appropriate depends highly on the use case.

MongoMallard also includes a SafeReferenceListField which will never return

invalid references in lists.

Lazy documents and proxying references

We already mentioned that a ReferenceField returns a lazy document. However,

what if we use inheritance? Let's assume the following document structure:

class Activity(Document):

lead = ReferenceField(Lead)

meta = { 'allow_inheritance': True }

class Email(Activity):

subject = StringField()

class Call(Activity):

phone = PhoneField()Let's further assume there is a ReferenceField which references the Activity

collection. We want to be able to access obj.activity.id without doing a

database request. However, since a reference doesn't store the class of the

referenced object, obj.activity.__class__ needs to do a database request to

evaluate the object. How can we make this work? The answer is proxy objects. A

proxy object is a wrapper which passes all or most calls to the underlying

object. In our case, everything except for the ID field is being proxied.

Our proxy class is based on werkzeug's LocalProxy class and is initialized

with the base document class and ID. Here is an excerpt:

class DocumentProxy(LocalProxy):

def __init__(self, document_type, pk):

object.__setattr__(self, '_DocumentProxy__document_type', document_type)

object.__setattr__(self, '_DocumentProxy__document', None)

object.__setattr__(self, '_DocumentProxy__pk', pk)

object.__setattr__(self, document_type._meta['id_field'], self.pk)

@property

def __class__(self):

# We need to fetch the object to determine to which class it belongs.

return self._get_current_object().__class__

def _get_current_object(self):

if self.__document == None:

collection = self.__document_type._get_collection()

son = collection.find_one({'_id': self.__pk})

document = self.__document_type._from_son(son)

object.__setattr__(self, '_DocumentProxy__document', document)

return self.__document

def pk():

def fget(self):

return self.__document.pk if self.__document else self.__pk

def fset(self, value):

self._get_current_object().pk = value

return property(fget, fset)

pk = pk()- The

LocalProxyparent class forwards all operations to the underlying object which is fetched using_get_current_object. In our case this performs a lookup in the database based on ID. - If we access the ID field (

pkis an alias for the primary key field,document_type._meta['id_field']is the actual name of the field, in our caseid), it returns it directly without doing a database lookup. - If we access the class (e.g. using

isinstance), the object will be fetched. Note that for an activity, bothisinstance(obj, LocalProxy)andisinstance(obj, Activity)will be true, but Python's implementation will only call__class__if we check for the latter, or if we check for any other class. That way we can check if we're dealing with a proxy object without doing a database request.

Note that we only use proxy objects if the document has allow_inheritance set

to true, otherwise we just return a lazy document object.

Other differences

You can read about all the differences between MongoEngine and MongoMallard in the DIFFERENCES file.

Benchmarks

How much faster did MongoMallard get? Here are some benchmarks that compare the speed of MongoMallard and MongoEngine:

Sample run on a 2.7 GHz Intel Core i5 running OS X 10.8.3

| MongoEngine 0.8.2 (ede9fcf) | MongoMallard (478062c) | Speedup | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Doc initialization | 52.494µs | 25.195µs | 2.08x |

| Doc getattr | 1.339µs | 0.584µs | 2.29x |

| Doc setattr | 3.064µs | 2.550µs | 1.20x |

| Doc to mongo | 49.415µs | 26.497µs | 1.86x |

| Load from SON | 61.475µs | 4.510µs | 13.63x |

| Save to database | 434.389µs | 289.972µs | 2.29x |

| Load from database | 558.178µs | 480.690µs | 1.16x |

| Save/delete big object to database | 98.838ms | 65.789ms | 1.50x |

| Serialize big object from database | 31.390ms | 20.265ms | 1.55x |

| Load big object from database | 41.159ms | 1.400ms | 29.40x |

See tests/benchmark.py for source code.

What next?

We realize that maintaining multiple forks is a bad idea, therefore our goal is to bring as many changes as possible upstream. We're working together with MongoEngine's maintainer so that a lot of our improvements will hopefully land in MongoEngine 0.9.

Comments

See Hacker News for comments: https://news.ycombinator.com/item?id=5979150