Connecting To Data Stores The Robust Way

We've recently run a deep investigation into how connections to our data stores are maintained, and how our tech stack interacts with them. This led to more resiliency in the face of failures as well as smoother proactive failovers. This post is a summary of everything we've learned in the process.

The big takeaway is that, when thinking of connections to any external resources, you need to ask yourself several questions:

- How long do we wait for a connection to be successfully established?

- How long do we wait for a request to be acknowledged/replied to?

- For how long can a connection go idle before we have to check its health?

- Do we or do we not block when the connection is being established or when information is communicated over the connection?

The answer to these varies depending on the data store and how your application talks to it. This post will talk about our tech stack, but some of the learnings are generalizable to others as well.

The problem

We had noticed that, sometimes, after a failover in our PostgreSQL cluster, some of our processes would hang for a long time – even as long as 15 minutes – and even if the database itself recovered much quicker.

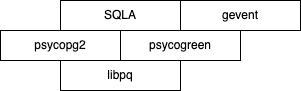

At a glance, this did not make sense. We had already configured a timeout of 10

seconds for establishing a connection to the database (via

SQLAlchemy → psycopg2

→ libpq → its

connect_timeout parameter).

We should never have to wait for more than 10 seconds then... Or should we?

Green threads, C extensions, and non-obvious overrides

The main concurrency engine we currently use at Close is gevent. It uses so called user-space threads, also commonly called "green threads", "coroutines", "greenlets", etc. Kernel-space threads are managed by the kernel, can be spread among several CPU cores, and can actually run in parallel. User-space threads, on the other hand, are managed by the application itself, and the kernel is completely ignorant of their existence. As a consequence, they can't run truly in parallel because they are scheduled to run in the context of the process that they exist in.

The point of using user-space threads is that they cooperate more seamlessly among themselves than kernel-space threads – they always yield when they can't proceed. Because of that, they are not preempted in favor of other threads at arbitrary times, and, because of that, they also don't need to worry about races as often. If you are accessing some shared data, but you won't be doing any operation that yields to other threads (for example, network I/O), you don't need to lock resources because you know you won't be preempted.

gevent achieves that objective by patching the Python standard library with code that is cooperative. For example, standard I/O operations like reading from and writing to files/network always yield to other greenlets instead of blocking. The original greenlet is queued to run again once the operation returns.

But gevent only knows about the Python standard library. It won't patch code that performs blocking operations via other means, like C extensions. Every library that you use with gevent must be able to cooperate with the other greenlets, either via the Python standard library, or its own code must be aware of gevent, otherwise it might block all other user-space threads.

psycopg2 uses a C extension to be able to use libpq under the hood, and connections to the SQL store are made via that C extension. This means that every network I/O operation performed by psycopg2 is invisible to gevent and will block the entire process. To fix that, we must patch psycopg2 in a way that makes it cooperate with gevent, and that's where psycogreen comes into play. psycogreen patches psycopg2 and makes it cooperate with gevent.

There is a non-obvious gotcha here though… To make a non-blocking network I/O,

psycogreen uses a different function than what psycopg2 uses by default.

psycopg2 uses the synchronous

PQconnectdb

to connect to PostgreSQL, but psycogreen uses two different functions:

PQconnectStart and PQconnectPoll. While PQconnectdb supports

connect_timeout, the PQconnectStart-PQconnectPoll combo doesn't. When

connect_timeout is not in effect,

libpq documentation

states that it will wait forever until the connection is established.

This means that, for processes that are not patched by gevent, connect_timeout

applies cleanly and, indeed, those processes will wait for just 10 seconds when

attempting a connection. But for processes that are patched by

gevent/psycogreen, libpq will wait forever.

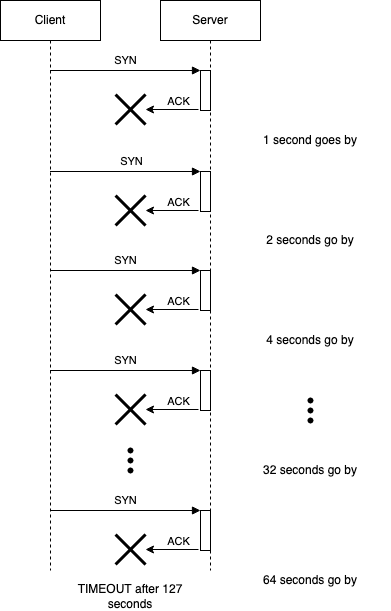

Well, libpq will. The TCP stack won't. In Linux, the TCP stack will start

retransmitting the SYN packet with an exponential backoff up to a number of

retries, and then give up. How many tries you get depends on what your specific

Linux system has defined as its default value for net.ipv4.tcp_syn_retries.

For our production Linux systems, that value is 6, which makes connection

attempts time out after 127 seconds (in practice, it translates to a little

more, since there are jitter and processing delays).

This is fixed by TCP_USER_TIMEOUT: if the connection takes more than X seconds

to be established, the TCP stack will give up and notify the application. The

libpq library accepts a tcp_user_timeout argument, which can be sent via the

SQLAlchemy interface. The libpq itself relays that value to the TCP stack.

That said, if the TCP connection succeeds, but the PostgreSQL connection fails to be established, then libpq will still wait forever. We couldn't find a way to fix this with just configuration. libpq's documentation suggests that the application should implement a waiting method.

Waiting for a response from a dead server

We covered establishing a connection to the SQL store. But what about waiting for a reply from the server on an already established connection? We mentioned that some processes would hang for as long as 15 minutes, but a connection attempt would time out after only 127 seconds (i.e. a little over 2 minutes).

The thing is: the TCP stack, by default, on most Linux systems, will wait for up

to 15 minutes for a data packet to be acknowledged by the other side. To be more

precise, 924.6 seconds. What happens here is that the TCP stack will retransmit

the packet for a number of times, defined by net.ipv4.tcp_retries2, and it

defaults to 15 in most Linux systems (again, an exponential backoff applies).

That translates to 924.6 seconds of waiting. You can read more details about how

that happens

in this blog post.

The gist is: when a server on the other side of your connection suddenly dies,

and it doesn't have time to send a FIN or an RST packet, your client is left

with a connection to nowhere. Sending packets into that connection will yield no

response, no matter how many times you try.

The problem also manifests itself when a server goes away for some time, for whatever reason, and then comes back. If the TCP stack is late in the retransmit phase, it might wait for a long time, for up to two minutes, before retransmitting again, which would also be undesirable.

We also fix that situation with TCP_USER_TIMEOUT: a TCP socket with that

setting will wait X seconds for a data packet to be acknowledged by the other

side before giving up on the connection and letting the application know that

the attempt to communicate failed and the connection is not good anymore.

Idle connections need to be inspected

If we have applied all the above measures, then our process should never wait for more than 10 seconds after an attempt to establish a connection or otherwise communicate. But if a connection can go idle for a long time, and the other side dies while the connection is idle, the application will need to wait for 10 seconds after trying to use the connection, to finally learn the connection is dead.

Could we do something to make the TCP stack aware that the connection is dead before the application attempts to use it, so that when it does, the TCP stack can immediately let the application know the connection is not good, instead of waiting for those 10 seconds? Yes, we can. That's where TCP keepalives come into the play.

With TCP keepalives, we can tell the TCP stack: if this connection goes idle for X seconds, probe the connection Y times. If the probes are not acknowledged, the TCP stack will declare the connection dead, and let the application know it immediately when it tries to use the connection.

The final configuration

Here's what we ended up with after all of the issues above have been tackled:

from sqlalchemy import create_engine

engine = create_engine(

"postgresql+psycopg2://user:password@hostname/database_name",

connect_args={

# Maximum time to wait while connecting, in seconds.

"connect_timeout": 10,

# Number of *milliseconds* that transmitted data may remain

# unacknowledged before a connection is forcibly closed.

"tcp_user_timeout": 10_000,

# Whether client-side TCP keepalives are used. 1 = use keepalives,

# 0 = don't use keepalives.

"keepalives": 1,

# Number of seconds of inactivity after which TCP should send a

# keepalive message to the server.

"keepalives_idle": 5,

# Number of TCP keepalives that can be lost before the client's

# connection to the server is considered dead.

"keepalives_count": 5,

# Number of seconds after which a TCP keepalive message that is not

# acknowledged by the server should be retransmitted.

"keepalives_interval": 1,

},

)An important note

It's important to note that every proposed solution here wasn't about avoiding an exception or even fixing the connection. Yes, you will detect a dead connection more quickly with this approach, but you still need to decide how you're going to handle the issue once detected. Raise an HTTP 500 error and let the client deal with it? Reestablish the connection and retransmit the data? Up to you...

If you want to recover without an exception, you need to implement this logic. Your stack may or may not offer something. For example, SQLAlchemy offers what they call "pessimistic" connection handling, which is a way to detect a dead connection when checking it out from the pool, and reestablishing the connection before handing it to client code completely transparently. The client code will never know it would have gotten a broken connection in the first place. This plays nicely with TCP keepalives, since if a connection was idle in the pool for a long time, the pool would immediately learn the connection was dead and reestablished the connection upon checkout, without any delays.

Other data stores

The same principles applied above can also be applied for other data stores:

- MongoDB: If you are using PyMongo, you probably already have a reasonable

default behavior. PyMongo will time out after 20 seconds of waiting for a

connection to be established. It uses an application-level heartbeat to verify

that the server is alive, sends it every 10 seconds, and it times out after 10

seconds, even while waiting for a response to a query. Those options are

connectTimeoutMSandheartbeatFrequencyMS. - Redis: If you are using redis-py, it offers a few options:

socket_connect_timeout: How long, in seconds, to wait for a connection to be established.socket_timeout: How long, in seconds, to wait for a response from the Redis server. Note that this is similar, but not the same asTCP_USER_TIMEOUT. The Linux feature is waiting for a TCP ACK packet. The Redis one is waiting for a Python-level socket operation to return, like thesend*functions and therecv*functions.socket_keepalive: A boolean value for whether TCP keepalives should be enabled.socket_keepalive_options: A dictionary mapping TCP keepalive options (socket.TCP_KEEPIDLE,socket.TCP_KEEPCNT, andsocket.TCP_KEEPINTVL) to their values. These options are analogous to the ones we saw above.

There's also other matters that need to be taken into consideration when thinking about this kind of problem, like SQL proxies, MongoDB routers, etc. They all can affect, positively or negatively, how connection failures are handled by your application.

What if your application-level technology lacks configuration options?

A last resort can be to configure the OS-level TCP stack options. For Linux,

this can be made at the host-level via the sysctl command, or, if you are

using Docker, can be configured at the container-level (effectively making these

options available per process).

The options that matter to us in this context are these:

net.ipv4.tcp_syn_retries: How many times to retransmit a SYN packet before giving up on establishing the connection.net.ipv4.tcp_retries2: How many times to retransmit a data packet before giving up on the communication attempt and the connection.net.ipv4.tcp_keepalive_time: How long a connection needs to be idle for before we start probing its health with TCP keepalive probes.net.ipv4.tcp_keepalive_probes: How many probes to send for an idle connection.net.ipv4.tcp_keepalive_intvl: How long between each probe and how long until the last one times out and the connection is declared dead.

The waits, timeouts and algorithm used for the retries are not configurable, as they are hardcoded in the kernel code. See this blog post for more detail.

You can find more information about those options, and generally the Linux TCP stack, here.